Kent Matthews ( The Conversation) | The People’s Bank of China is encouraging Chinese banks to lend more to businesses and consumers by cutting the proportion of deposits that they have to hold as reserves by 0.5 percentage points to an average of 8.4% from December 15.

It follows a similar cut in July, and is an interesting counterpoint to western central banks such as the Bank of England and Federal Reserve. They are talking about tightening monetary conditions to dampen inflation by raising interest rates and reducing quantitative easing, which effectively creates more money to stimulate lending.

So why are the Chinese loosening and what effect will it have?

China’s growth headache

The official reasoning is to ease credit conditions in the face of a slowing property sector and a disappointing annual GDP growth rate of 4.9% in the third quarter, down from 7.9% in the second quarter. The cut in the bank reserves minimum, which is known as the required reserve ratio or RRR, is expected to release ¥1.2 trillion (£143 billion) of extra money into the economy.

This aims to bolster demand within China so that the modest government growth target of 6% in 2021 will be met. It could achieve that short-term goal by stimulating demand if credit expands and gets to the right places. And, unlike the west, inflation is less of a problem in China because the money supply has been growing slowly.

Despite the hype about China bouncing back from its lockdown experience, the pandemic has not helped its economic situation. Like the rest of the world, it has encountered major supply disruptions. Some has been domestically driven but most is global, with shortages of electronic chips, coal, steel and shipping capacity causing power shortages and shutdowns.

But these are short-term problems that may dissipate as the pandemic eases. Unfortunately, there are also long-term issues that tinkering with the RRR will not solve.

Pillars wobbling

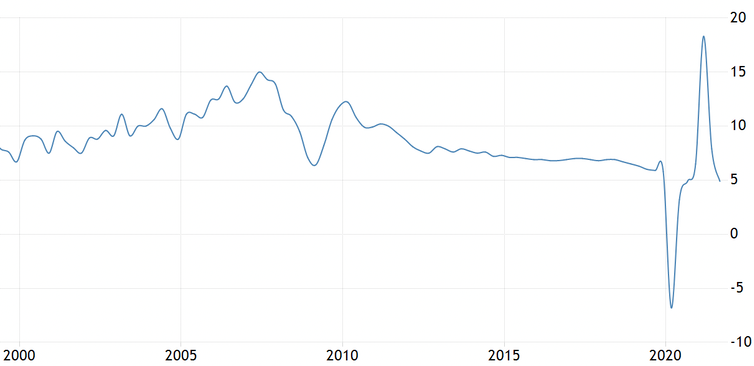

Growth in China was in fact declining well before the pandemic struck: from a peak of 15% in the second quarter of 2007 to 6% in the first three months of 2019. The nation’s growth strategy rests on four pillars. Three are frequently talked about – infrastructure, exports and consumers – while the fourth is only whispered in official circles – and that is the property sector.

The property sector supports 25%-29% of China’s GDP and it is struggling. With major players such as Evergrande overloaded with debts and struggling to stay viable, prices for new homes are falling and construction has greatly slowed.

Nor is property the only economic pillar on shaky ground. Infrastructure spending led by local government and large-scale projects headed by state-owned companies served the Chinese economy well in decades gone by. But then came the global financial crisis of 2007-09, which prompted a ¥4 trillion fiscal stimulus package in 2008. China’s money supply increased by nearly 30%, leading to a doubling of stock prices and a property boom.

Beijing started restricting credit in 2009 in ant attempt to curb this overheating. One consequence was that banks started devising alternative financing vehicles – the Chinese variety of what is known as shadow banking – that diverted money into local government spending on infrastructure and property.

This meant infrastructure spending continued, but it produced rapidly declining returns for the economy, because much of it was unnecessary. Tens of millions of apartments were built, even entire ghost cities, for workers that never arrived. Where previously migration flowed from rural areas to towns, this has dried up. Real estate investment growth reached a peak in 2013 and continues to grow – but at a lower pace.

Exports, on the other hand, still do drive growth, since global supply chains remain dependent on Chinese manufacturing. But China’s rising cost of labour has meant that profit margins are often very thin, adding little value to the economy, and manufacturers are susceptible to being wiped out by movements in the yuan and volatility in global demand.

The trade war kicked off by the Trump administration, which has broadly continued under Joe Biden, has shown China that the old export-led growth model is unreliable and it needs to move up the value chain by focusing more on exports with higher value-added (meaning products where there’s a bigger difference between the cost of production and the sale price). Many low value-added operations have already relocated to Bangladesh, Vietnam and Indonesia.

At the same time, China’s “one-child” policy and the preference for male babies has led to a decline in fertility and population growth. China’s population is expected to peak between 2025 and 2030, or perhaps sooner.

The dependency ratio – the ratio of non-workers to the working population – has already been rising for at least a decade and is expected to continue doing so. As the working population declines and the consumer demand of young and retired dependents keeps increasing, China’s consumption will outstrip economic output.

The turn inwards

Under the guise of “common prosperity”, the government is signalling that the private sector is to be brought into the orbit of state control. It has clamped down on shadow banking and the peer-to-peer lending platforms that have been the lifeline for many small businesses, since most bank lending is restricted to state-owned enterprises.

The government has also introduced restrictions in areas such as the tech sector, out-of-school education and overseas stock market listings. And the message to the global capital markets is that China does not need foreign finance unless it is investment with expertise and know-how.

Foreign investors have naturally reacted with alarm to all this intervention, dumping Chinese stocks and withdrawing exposure to China. There are several possible interpretations of this chain of events: China may have genuinely underestimated the reaction of global investors, or it might all be a carefully thought-out strategy brought forward by the pandemic.

For some time, China has been talking about re-balancing away from exports towards domestic growth. While infrastructure spending has clearly produced mixed results, domestic consumption can be stimulated if Chinese manufacturers reduce their dependence on overseas customers and focus closer to home.

The pandemic and the government’s zero-COVID policy have given it the opportunity to steer the economy away from the outward-looking opening-up strategy pioneered by Deng Xiaoping in the 1980s to a more inward-looking strategy under Xi Jinping today.

The term “dual circulation”, in the sense of unlocking China’s economic potential at home and abroad, has been used by the administration to hide a desire for greater self-reliance in technology, energy, finance and education. This will have far-reaching consequences for the world economy, not least for UK universities dependent on future Chinese students.

In Chinese Looking Glass, the 1969 book by British journalist Dennis Bloodworth, he explains Chinese policy deriving straight out of its ancient Taoist philosophy of yin and yang. In foreign policy China first “awes” (yang), then “soothes” (yin).

Threatening the private sector in China and scaring foreign investors may be part of the yang strategy. Once the economy shows signs of rebalancing towards domestic expenditure, we may see the yin strategy.