Miguel Navascués | Recently, in the US, long term interest rates have fallen below short term rates. This has a more concrete significance: the economy is getting weaker and could enter recession. Something unusual has happened which we must explain.

Bond investors, which are principally large houses which buy for themselves and their clients, base their decisions on their expectations. They observe the market and decide to buy or sell according to their expectations in the short and long term about various aspects of the market and its future. When the economy starts to weaken is when an inversion of the yield curve can occur. Why? Because the long term expectations for the economy and inflation worsen: a fall is expected in both. Therefore, the expected returns fall because the buyer demands less returns to cover fewer risks, which causes demand for the bond to rise, and its price fall, at the same time that its returns in cash in the market falls.

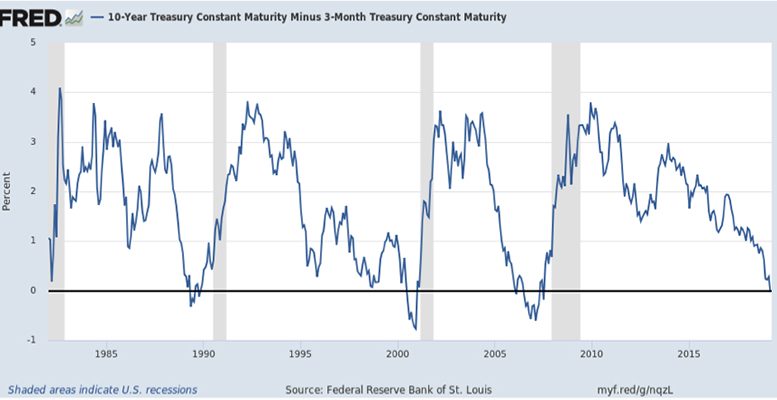

On the other hand, in the short term there is an increase in returns because people get into debt in the short term to buy in the long term, or sell their short term bonds to buy long term bonds. Therefore the short term returns rise, and long term returns fall, until the long term – short term spread, which is normally positive, becomes negative. A fall in this spread or differential is related to the generalised expectations of weakness, even recession, in the economy. In the diagram this behaviour is clear: the inverted returns slope, signalling a recession is likely.

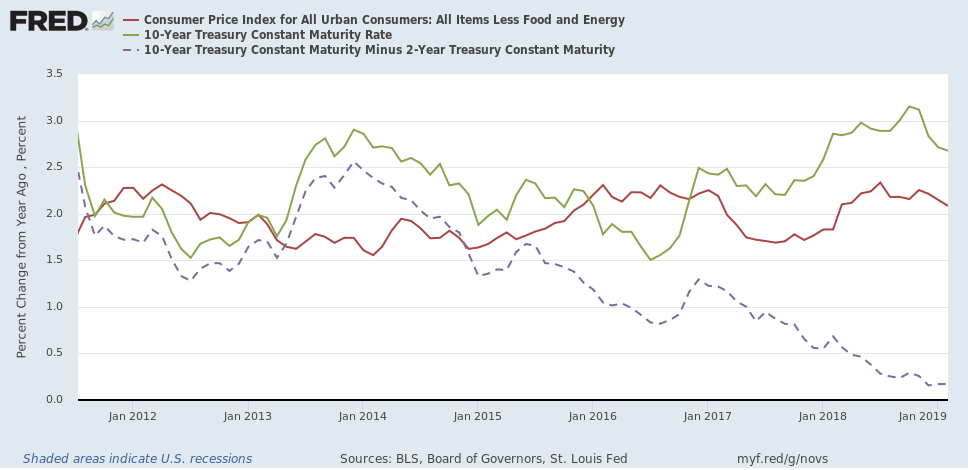

The red curve, which is the 10 year bond interest rate, by falling explains to us that expectations (growth + inflation) have recently declined; the green curve, which is expected inflation (I will not explain how this is obtained) shows a downward incline. In the opinion of the actors, the risk of inflation has reduced.

In the US the inverted yield curve has fairly regularly anticipated recessions. So it is likely that within a while we will see a recession, according to expectations. It must be taken into account that in the markets, the expectations feedback into themselves, and that when things take a direction it is difficult to reverse it.

If we just stop here we are over-simplifying. The problem, as Amin Rajan says (ex-Governor of the Bank of India and one of the few economists who predicted the crisis), is that:

“With QE, the capacity for the markets to self-cure has lost its power. The same with equities, which lacks a reasonable point of anchorage in risk free assets. The same warning is applied to the yield curve: the measurement of spread in interest rates (generally between 2 and 10 year US treasuries). In relative terms, history shows that the higher long term rate is destined to compensate investors for the inflationary consequences of a growing economy. On the other hand, a lower rate implies a lower risk premium if the economy is headed towards a recession.”

Indeed, we are in an anomalous context burdened by the consequences of the crisis, which will possibly continue to be evident for several years. On the one hand, central banks have pressured interest rates downward to incredible levels, and, on the other hand, this has had two consequences: an increase in indebtedness all over the world, and a dramatic rise in stock markets or fixed income. Both facts are related, given that low interest rates are an invitation to take on debt to speculate or invest, although fixed long terms investment, very risk, does not exactly stand out. These two facts, which has originated with the central banks, have boomerang consequences for them, as they seen themselves restricted in their monetary policy: if inflation increases, they will find it very difficult to raise interest rates, because it cause a global debt crisis and a fall in stock markets.

This leads us to predict a long period of low interest rates, a very prudent policy for the central banks, and a worrying scenario, which will demand a new monetary policy (as we explained in an article last month), which will allow higher inflation around an average of 2% – not excessive – and interest rates to become independent of central banks. In short, to allow the yield curve to return to its previous significance. In addition, the health of the banking sector demands that its profits increase, which would make interest rates rise. What is not advisable is to continue as we are, generating debt above the growth in wealth.