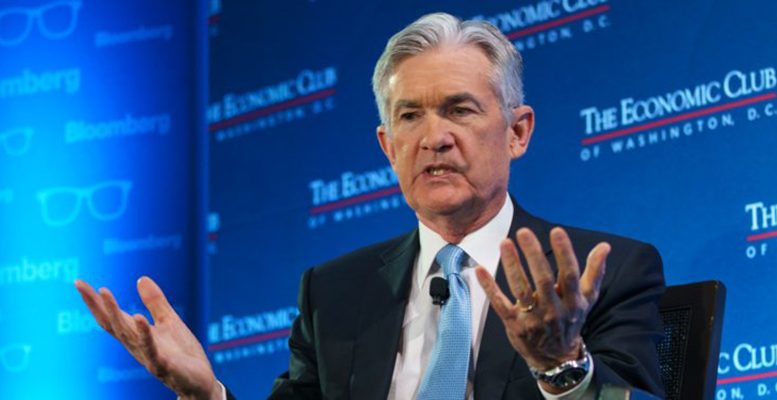

J.P. Marín-Arrese | The Fed kept rates on hold this week. Yet, Jerome Powell shattered hopes they had reached a ceiling, announcing in the press conference that an extra hike was in the pipeline before the year-end. Inflation is still running too high and will likely take much longer than expected to match its medium-term goal. Powell was at odds in justifying why rate stiffening has neither cooled the economy nor softened the tight labour market, thus fuelling sharp salary increases. He confessed to being unable to identify the culprit, while advancing as potential reasons the lag in monetary policy and the substantial holdings of businesses and households.

As Christine Lagarde rightly pointed out last year, higher rates don’t bring down gas prices. Nor a supply-led inflation such as the one fuelled by the wild commodity speculation that followed the invasion of Ukraine. Following conventional wisdom, Increasing the financial bill should put a brake on demand and output, thus alleviating price pressures. A hawkish monetary stance also helps to trim inflationary expectations preventing it from feeding second-round price hikes.

Why has the Fed’s stiffening failed to harness demand? Headline inflation has markedly eased, mainly due to the commodity scalping meltdown. Yet core inflation seems staunchly entrenched. Rates have so far proven unable to dent the strong economic performance the US is currently witnessing. The answer to this riddle may lie in the Fed’s reluctance to sell-off its huge portfolio at a speedy pace. Excess liquidity prevents monetary policy from fully influencing economic activity. While short-term yields are running high, long-term ones are lagging far behind.

Why does the Fed take such a lukewarm approach in performing its asset disposal plan? It fears destabilising the financial markets through a massive sell-off of the securities it holds. It also needs to monetise the extensive public deficits indulged to overcome the pandemic crisis. Rather than draining liquidity, it provides ample financial support to banks as their cash holdings dwindle. A strategy that flatly failed in the Great Inflation until Paul Volcker left the job of fixing the rates to the market while the Fed undertook a sharp reduction in money supply. The ensuing crash-landing is the scenario the Fed wants to avoid now. The price to pay will be higher inflation for a much longer time, risking falling into stagflation should the economy falter. The worse of all potential outcomes.