LONDON | Investment house Schroders brings in its latest ‘Economic and Strategy Viewpoint‘ the final word about austerity versus money printing. It is a conciliatory one. Well, sort of: chief economist Keith Wade and Europe economist Azad Zangana set the record seamless and believe each team is right, at least, about the other team: they all are wrong.

On one hand, Wade and Zangana say they hold the

“belief that fiscal austerity will not generate growth as imagined by the ‘troika’.”

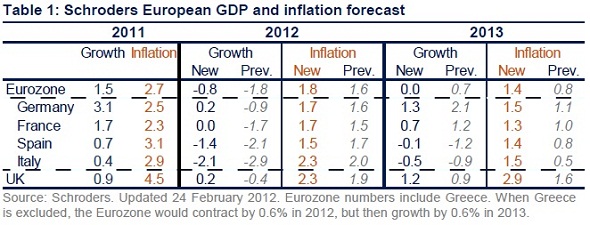

Both economists remind the champions of ever smaller state budgets that, in past periods, fiscal consolidation across a range of economies has only met success because the tightening occurred against a backdrop of buoyant global growth

“where monetary policy was able to provide an effective offset and exports provided the demand to support activity.”

Unfortunately, “today, in the wake of the global financial crisis, monetary policy is ineffective, export growth is scarce and there is a currency war as countries try to devalue their way to recovery.”

So that is a zero to zero score for this match. Schroders’ economists add that fruitful budget cuts in modern history tend to have been carried out by countries in isolation. What we are witnessing nowadays is a large percentage of the world introducing tightening policies almost simultaneously.

“The scope for spill-overs in this environment means that the fiscal multipliers will be greater than in the past.

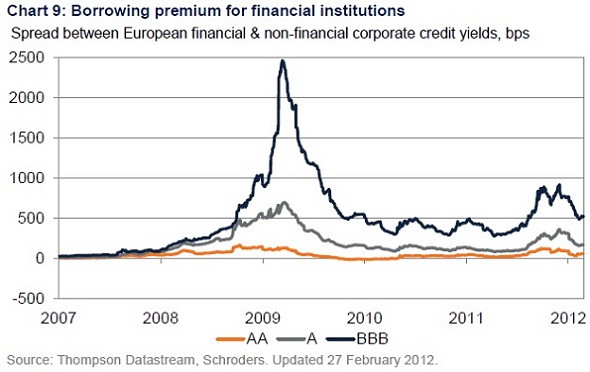

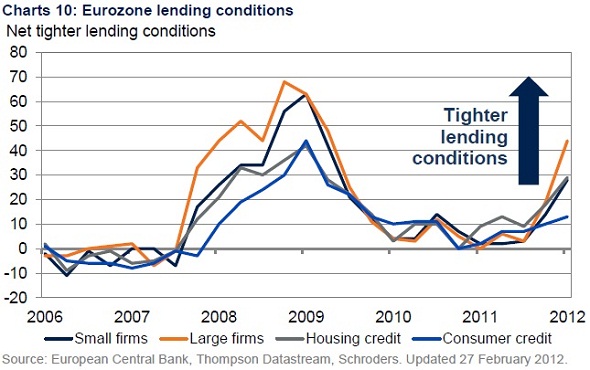

“Put these points to those driving the bailout (i.e. north European central bankers and officials) and they respond that the fall in interest rates generated by fiscal austerity will ‘crowd in’ investment and support growth. In normal times we would agree, but when credit mechanisms are broken there is little offsetting monetary impulse from lower interest rates.”

The description in the Schroders paper of our current travails is dire: we are left with weaker growth, a shrinkage of the tax base and market doubts about solvency. The problem is compounded in the euro zone by the inability to devalue by those country members that would require it. The consequence then is often higher interest rates as investors focus on default risks.

“Unfortunately there seems little prospect of the troika changing its mind.”

Is there a glimpse of hope, anywhere at all? Absolutely.

“What Greece really needs is a modern day equivalent of the Marshall Plan to reconstruct the economy, which is what she may get, but only after leaving the euro.”

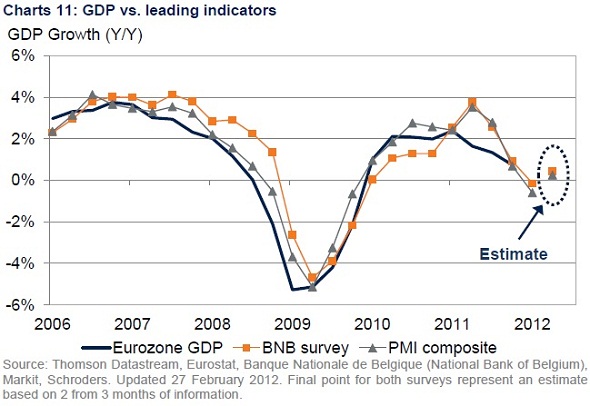

If you are prone to see the glass half full, and we at The Corner assume readers prefer cheer to despair, the following charts prove that the European Commission and the European Central Bank do have the capability to turn the tables around.

Be the first to comment on "Schroders: neither austerity, nor monetary expansion but a Marshall Plan"