Asad Zangana (Schroeders) | Very few will argue against the notion that most economies are in recession, and that this will be the largest contraction in economic growth recorded in modern times. Private business surveys have already hit record lows as they start to report the damage done by the Covid-19 crisis.

The scale of the fall in GDP is now less important for investors than the extent and speed of the eventual recovery. This of course is highly uncertain as discussed in a recent note: Economies in free fall as hopes fade for a V-shaped recovery. The note also discusses the permanent effects from the crisis, an area that requires more attention.

The first responsibility of any government is the protection of its citizens. The Covid-19 crisis is no different. Policymakers have been entirely focused on adapting social, health and economic policy to help their populations withstand the pandemic.

However, eurozone governments have also been forced to use a tremendous amount of time and energy considering how to help their fellow member states, especially peripheral countries that have essentially lost the confidence of the market without the intervention of the European Central Bank (ECB).

Governments need to borrow more in order to cover shortfalls in tax revenues and additional spending on social security and health. Deficits are very likely to surpass the highs seen during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), meaning that debt will surely rise to eye-watering levels.

For most countries, this is manageable with the help of monetary policy. However, in the eurozone, monetary policy, though loose, is limited in its ability to help. EU wide fiscal policy is currently moving much faster than its usual glacial pace, but there are still big questions about how countries will deal with the legacy costs of the crisis.

Some will see this as the end of the road for the “can kicking”. Bonds yields in peripheral Europe have been spiking, forcing the ECB to return with larger stimulus packages. The loose ends of the eurozone are exposed and are threatening to unravel the very fabric of the monetary union.

Italy is the prime candidate for being the first casualty. Its high indebtedness and lack of economic growth require policies that are either illegal in the eurozone, or politically unpalatable domestically. In this note, we discuss the key risks moving forward, the likely help on offer, and possible scenarios.

Italy is highly indebted and large

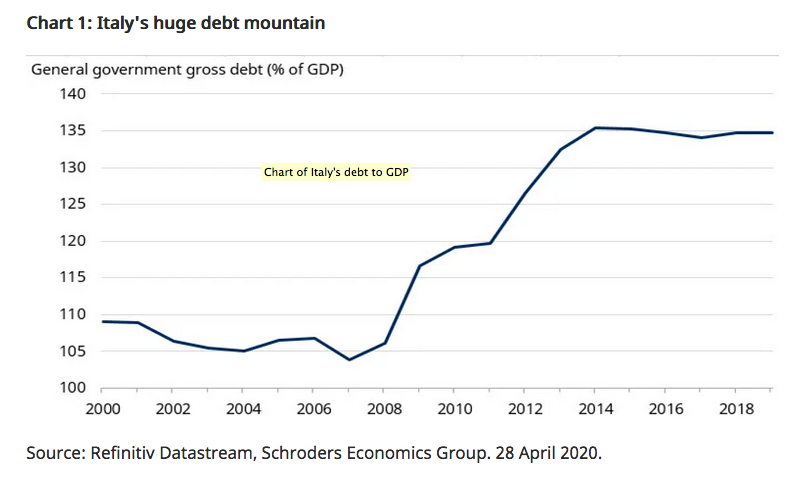

Italy stands out as the most likely candidate to exit the eurozone for several reasons. First, with gross debt estimated at 135% of GDP in 2019, it faces a significant challenge in both servicing its debt, but also refinancing it.

In the early years after joining the monetary union, Italy succeeded in lowering its gross general government debt from 109% of GDP to about 104% in 2007 (chart 1). However, the cost of the GFC and its aftermath pushed gross debt up to just over 135% of GDP by 2014, where it has largely remained.

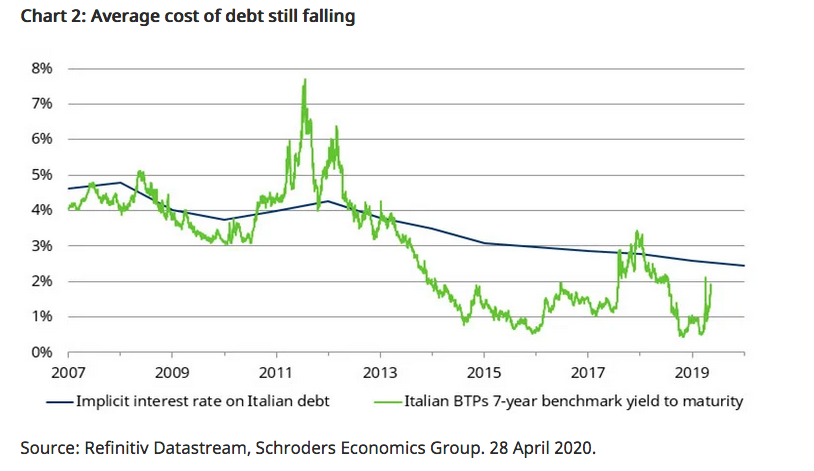

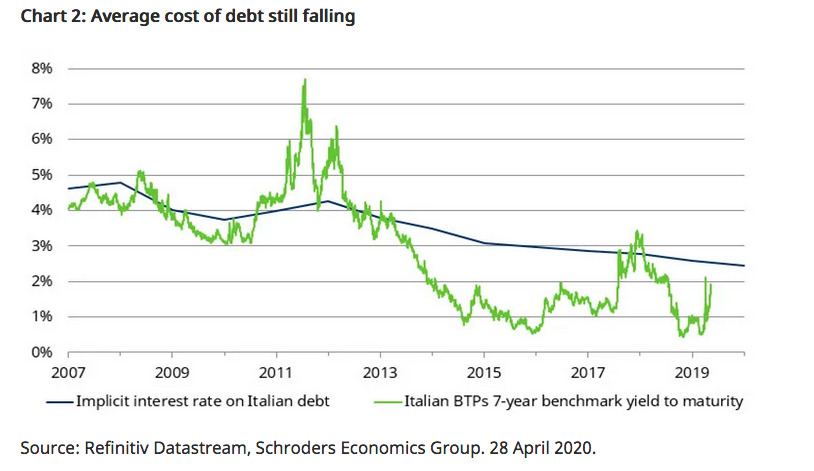

Fortunately, Italy has one of the higher debt maturity profiles in the eurozone, meaning that on average, it refinances its debt roughly every seven years. This has helped reduce the pressure of refinancing, but not without the help of the ECB through its quantitative easing programme, and other liquidity provision measures.

The recent spike up in Italian bond yields appears dramatic, but in fact, the yield on the comparable seven-year bond has remained below the average interest rate paid on existing debt. This therefore means that the average cost of Italy’s debt stock is still falling. The seven-year bond yield would need to rise from its current level of 1.8% to over 2.4% before it starts to have a negative impact on Italy’s public finances (chart 2).

Despite being highly indebted, Italy is not the most indebted member state. Greece continues to hold that unenviable title despite two rounds of debt restructuring. The reason why Italy is a concern and Greece is not is simple: Italy is too large to bail out.

When Greece, Ireland and Portugal found themselves in difficulty in the past, they were forced to borrow from the rest of Europe and the IMF. Together with the help of the ECB, they were able to avoid borrowing through the traditional use of market auctions for some time. This was possible as these member states were relatively small – together making up just 5.8% of euro area GDP in 2011.

Italy is almost three times larger those member states. As the eurozone’s third largest member, bailing out Italy would simply require too much capital, especially as this is happening at a time when all member states find themselves borrowing huge sums to cope with the crisis.

Not enough growth

Italy has always been very careful with its public finances, with policymakers mindful that its huge debt burden leaves little room to manoeuvre.

For example, through the GFC, its primary balance (budget balance excluding interest payments) only fell into deficit briefly in 2009 and 2010, troughing at only to 0.9% of GDP. This was incredibly restrained compared to other advanced economies, such as France (-4.9%), Spain (-10%), the UK (-8.7%) or the US (-11.3%) as shown in chart 3.

The Italian government’s reluctance to spend during the financial crisis arguably contributed to the country’s deep recession and lacklustre recovery. Indeed, this is evident from nominal GDP data since the GFC. The reason we focus on nominal and not real GDP growth is that public finances and debt are measured in nominal terms, therefore inflation is just as important as real growth in this respect.

Since joining the euro, Italy had managed to keep up with the pace of eurozone nominal growth; however, since 2009, Italy has only managed just over half of the growth achieved by the eurozone aggregate (chart 4, above).

The lack of growth in Italy is one of the fundamental reasons for its poor public finances, and why it is approaching the point where its debt becomes unsustainable. Even before 2009, though Italy was growing at a reasonable rate, it was doing so with poor productivity growth and losing competitiveness in international markets. During the GFC and the subsequent European Sovereign Debt Crisis, Italy failed to reform its labour markets and follow in the success of Ireland, Spain and Portugal in regaining competitiveness.

Poor growth dynamics make it very difficult for a country to service its debt. While Italy’s marginal interest rate is falling, as discussed above, it remains higher than the growth rate achieved in seven out of the past ten years. This is why Italy has been forced to run a considerable primary surplus just to slow the rise in debt as a share of GDP.

What is the impact of the Covid-19 crisis?

Turning to the immediate outlook, the Italian government presented its updated fiscal forecast for 2020 and 2021 on 27 April 2020. The budget deficit is forecast to rise from 1.6% of GDP in 2019 to 10.4% of GDP in 2020, before falling back to 5.7% for 2021. This assumes real GDP contracts by 8% this year before rising by 4.7% in 2021.

As for debt as a share of GDP, it is forecast to jump from 134.8% of GDP in 2019 to 155.7% by the end of this year, before declining to 152.7% in 2021. Compared to consensus estimates, the government has a similar growth forecast but is assuming a much larger deficit.

At this point, any forecast has to be treated carefully. But for Italy, even before the crisis, concerns were mounting over its demographics. Italy’s working-age population has already begun to shrink. Taken together with poor productivity growth and a lack of willingness to reform, these factors spell trouble for Italy’s trend rate of growth going forward.

In other words, Italy was likely to experience a sovereign debt crisis over the next decade before the Covid-19 crisis hit; that time frame may now have been brought forward to the next few years.

What help is on offer?

At present, investors continue to own Italian government bonds in large scale, partly thanks to interventions from the ECB, and more recently, help being offered centrally through the European Union. Starting with the central bank, the asset purchase programme (APP – the ECB’s main quantitative easing programme) continues to accumulate assets at a pace of €20 billion of purchases per month.

At the March Governing Council meeting, the announcement was made that an additional temporary envelope of €120 billion would be added for this year.

However, this did not seem to satisfy investors. As the spread between Italian and German government bond yields hit 3%, the ECB rushed out an announcement that a further €750 billion of purchases would take place by the end of the year under the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP).

The announcement of the PEPP was deliberately ambiguous over certain key features or limitations. Part of the challenge for the ECB is that its justification for its QE programmes is to tackle the risk of deflation, not to bail out particular member states. In the same fashion, the targeted long-term refinancing operations (TLTROs) are there to encourage greater lending to banks by offering cheap financing, rather than being offered to bail out banks. The fact that both do the latter is a happy co-incidence or side effect.

For this reason, QE programmes are meant to be allocated according to the ECB’s capital key – a schedule based on how much capital each member state has put in or pledged for the running of the ECB, which is proportional to the size of member states by GDP.

For most investors, Italy’s precarious public finances are seen as the biggest risk to the stability of the monetary union. Hence, any form of stimulus that aids Italy would be welcomed. In its announcement, the ECB stated that “…purchases under the new PEPP will be conducted in a flexible manner”, referring to the capital key. However, the legal documents that followed clearly stipulate that purchases would adhere to the capital key, and that flexibility would merely be offered on the timing of when purchases should fall in line with the capital key.

This is nothing new, as the APP has the same flexibility, especially as some member states choose to issue debt earlier in the calendar year compared to others.

What about the fiscal response?

There was a lot of pressure on the ECB to act decisively as market expectations of an EU wide fiscal response were very low. Despite this, the EU quickly moved to suspend fiscal rules, allowing member states to exceed the Maastricht Treaty criteria levels and paving the way for large and comprehensive fiscal packages from most member states.

Italy’s fiscal response has been slower and smaller than announced elsewhere with policymakers clearly concerned over the rise in borrowing costs. Instead, Italy’s prime minister, Giuseppe Conte, demanded greater solidarity to be shown across Europe. The response, which was recently approved by the Eurogroup, was to enable the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) fund to provide €240bn of loans up to 2% of GDP of the borrowing member state.

The ESM was set up at the tail-end of the Sovereign Debt Crisis in order to offer temporary relief for countries that find themselves shut out from financial markets. However, use of the ESM requires a memorandum of understanding, which includes commitments from the borrower to introduce fiscal, financial and economic reforms.

Though some of the conditionality has been relaxed, use of the ESM would be toxic in Italian politics, as many argue that there should be no stigma attached to requesting help, and the funds should be delivered as aid rather than a conditional loan. It may not be Italy’s fault that the Covid-19 virus has debilitated the economy, but hawks would argue that by going into this crisis with terrible public finances, Italy has nobody to blame but itself.

In addition to the deployment of ESM funds, a €100 billion new loan fund would be set up to help pay for the furlough of staff (called “SURE”). €25 billion of credit guarantees from the European Investment Bank (EIB) would be made available for commercial banks to leverage up and lend out to struggling small and medium sized enterprises.

With Italy threatening to vote against the overall package, the change in position probably only came once Germany had signalled that it would support a centrally funded EU recovery fund designed boost growth once lockdowns are over. France’s president, Emmanuel Macron, agrees, stating in a recent interview that “You cannot have a single market where some are sacrificed. It is no longer possible . . . to have financing that is not mutualised for the spending we are undertaking in the battle against Covid-19 and that we will have for the economic recovery.”

At this point in time, no official details of the creation of such a fund have been released. Rumours suggest it could use around €400 billion-€500 billion of capital/commitments to provide banks with credit that would then be leveraged up four to five times. If this is true then it is a questionable strategy. Banks are highly unlikely to want to increase their leverage even further, especially as the economy will still be struggling, and defaults will increase (even if a proportion of loans are backed by governments).

Politically, the bigger question will be whether the fund distributes according to national shares of GDP and whether the funds are deemed loans or grants. Creditor countries would prefer the former as it provides an illusion of control over the eventual repayment. In reality, the loans will be very long-term loans at near zero interest rates, which may as well be called grants at that point, hence the delay in any agreement given obvious opposition from Northern European member states.

Will the help be enough for Italy?

Taking both the fiscal and monetary support on offer, Italy should be able to refinance its maturing bonds comfortably this year. However, if the ECB does not extend its additional QE programmes into next year, then Italy is very likely to see yields drifting higher. Investors will demand a higher premium for buying debt from Italy given its terrible public finances and poor growth outlook.

At some stage, potentially in 2021 or 2022, austerity is likely to become politically impossible which will scare international investors into selling their holdings and potentially prompting a debt crisis. A reckoning could take place where the EU finally decides if it is prepared to mutualise debt across the monetary union.

If it does, then the problem goes away for a while, but not forever. Countries like Italy will refuse to accept fiscal oversight, and so at some point in the future, the same behaviours and poor growth will cause a larger crisis, only this time, Germany, France and everyone else will be jointly liable. For this reason, debt mutualisation is highly unlikely.

In the absence of debt mutualisation, Italy has two options:

First, it can swallow its pride and enter into an ESM programme, which could also trigger Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) from the ECB. This would allow the ECB to exclusively buy Italian debt. However, this would mean heavy scrutiny and insistence on reforms. Italy would probably have to restructure its debt, essentially defaulting on both its people and international investors. This would work in the short-term, but as we have seen in Greece, would only stabilise the situation. It is not a panacea, and there would be grave political consequences as a result.

The second option would be to reject help and leave both the eurozone and European Union, with debt converted to the new Italian lira, triggering technical defaults. This would also allow Italy to devalue its currency and repair its competitiveness. Higher inflation and growth will go a long way to stabilise public finances, though the human cost and the erosion of private wealth would be enormous.

The direction of travel between these options will depends on the politics at that point. When faced with this choice, Greece chose to remain in the euro and defaulted (twice). Its past experience of large currency devaluations and high inflation were still fresh in the minds of voters.

For Italy, the politics may not be as helpful, with two of the three biggest parties both openly questioning the value of the euro project in the past. Even the most europhile policy makers cannot deny that the risk of Italy leaving the euro is now very high, which also raises questions over the future of the euro.