Irene Lauro (Schroders) | According to the World Meteorological Organization, the past six years (2015–2020) were the warmest on record, with the global average temperature rising 1.2° Celsius above the pre-industrial level.

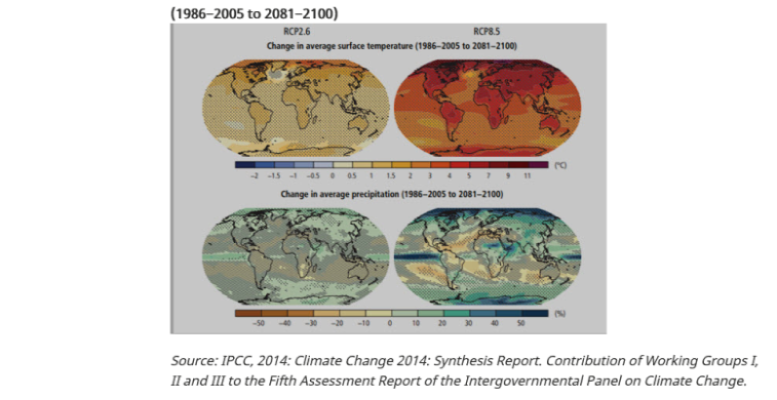

But while climate change is affecting all regions around the world, global warming and precipitation rates will not be distributed evenly around the globe. There will be winners and losers.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has sought to better understand the precise risks of climate change. To do so, it has modelled the amount of greenhouse gases (GHG) we are producing to generate numerous climate change scenarios – or trajectories – called representative concentration pathways (RCPs). Each scenario corresponds to a different level of warming.

Overheating economies?

RCP2.6 is a “best case” scenario. In this scenario, GHG emissions are cut back sufficiently, such that global warming is capped at around 1.5 to 2 degrees above the pre-industrial average. At the other end of the scale is RCP8.5. This is a “worst case” scenario. It reflects “business as usual”, in which no effort is made to rein in emissions. The scenario outlines global temperatures increasing by 4 degrees compared to the pre-industrial average, by 2100.

The IPCC highlights that – as shown in the Chart above- all countries are likely to see higher temperatures by the end of the century, but global warming will be more severe in some regions of the world. The economic impact of climate change will therefore also vary, having important repercussions for asset returns.

In particular, the Arctic region is expected to continue to warm more rapidly than the global average. Additionally, temperatures in higher latitudes of the Northern hemisphere will rise more swiftly than in the regions in the tropics.

Rainfall will also not distribute uniformly across the globe. It is expected to increase in regions at high latitude and in the equatorial Pacific, regions already affected by long monsoon seasons. It is expected to decrease in mid-latitude, subtropical regions, which tend to be arid areas.

This means that wet areas of the world are expected to become wetter as climate change intensifies, while water is likely to become less available in areas where the supply of water is already scarce. For example, India, Pakistan and Nepal are likely to see more severe monsoon seasons, while African and South American countries are likely to experience dryer conditions.

The impact of climate change on productivity

We have incorporated the economic impact of climate change into our long-term productivity forecasts. The methodology and implications for investors is explained in our 30-year return forecasts.

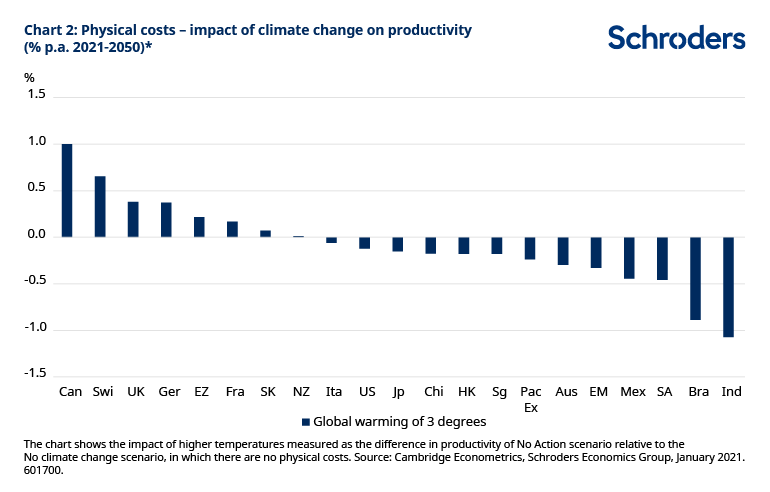

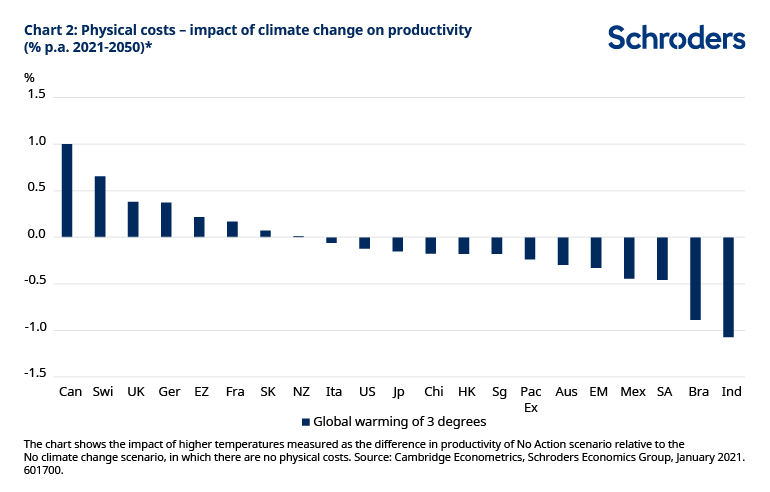

As highlighted by recent research by Burke and Tanutama, there is a quadratic relationship between productivity growth and temperature. This means that “cold country” productivity increases as annual temperatures increase, but where annual temperatures are higher than 12-13°C, productivity begins to decline.

For example, in cold countries an increase in temperature could open new areas to cultivation or more parts of the sea could become navigable and available for fishing as the ice melts. On the contrary, in hot countries agricultural output is expected to decline as a result of increased desertification. Livestock production will also diminish due to increased heat stress.

Chart 2 shows the physical costs in a scenario where global temperatures rise by more than 3 degrees Celsius by 2100 relative to the pre-industrial average. This scenario suggests world economies fail to implement adequate mitigation strategies to limit carbon emissions.

The costs are expressed relative to the “no climate change case”, where there are no temperature effects. On a 30-year horizon, Switzerland, Canada, Germany, France and the UK will all be better off in a scenario where global warming rises more than 3°C above pre-industrial levels. Productivity deteriorates in Australia and most emerging market countries.

The more visible consequences of climate change

It is not just over the long-term that climate change can cause economic damage. Extreme weather events show that there is a short-term impact too. Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, Katrina and Sandy have already shown how damaging climate change can be today. These are some of the most visible examples of the short-term consequences of a warming world.

It is a well-known fact that global warming has caused a significant increase in weather-related events over the past decades. For example, globally, the average number of tropical cyclones in a decade has gone from 14 to 23 since the start of the 1980s, while the number of floods has almost doubled. The IPCC highlights that risks associated with extreme events will continue to increase, with these events becoming more frequent and more disruptive as temperatures rise.

Extreme weather events, as they are strictly dependant on temperature and precipitation changes, will impact different regions of the world unevenly. Floods and tropical cyclones have increased in the past decades only in some areas of the globe. Chart 3 below shows the change in the average number of these events in the first decade of 2000 relative to the 1980s. It suggests that floods and tropical cyclones have become more frequent in South East Asia, consistently with the IPCC’s analysis.

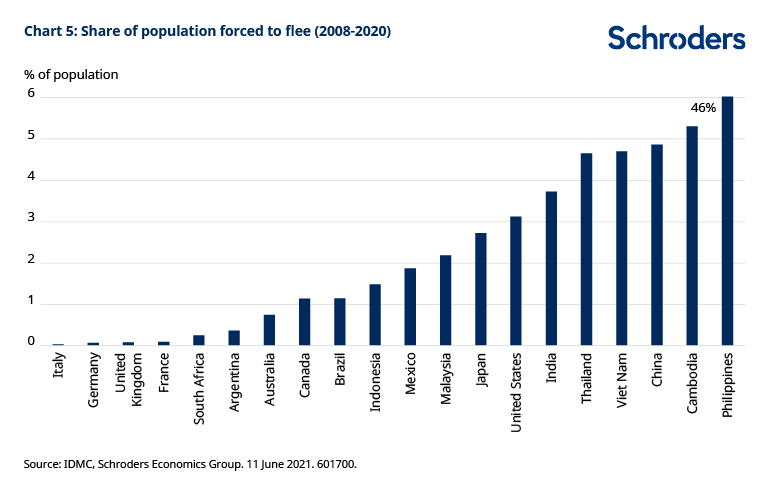

These events can have disruptive and devastating consequences for people. Data from the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre highlights that since 2008 almost 200 million people have been forced to leave their home, with floods and storms accounting for almost 98% of the cases.

More importantly, the data shows that inhabitants of some regions of the world have been hit more severely than others. In particular, inhabitants of the Philippines have been most at risk, with the number of new displacements reaching 46% of the population since 2008. The rest of South East Asia and China have also been affected by extreme weather, but also the United States and Japan. People living in European countries and in the UK have been the least subjected to displacements due to extreme weather.

Finally, it is worth highlighting that the data refers to displacements within the country, but we think it is reasonable to assume that internal migration is positively correlated with external migration. This could suggest that as global warming intensifies and extreme weather becomes more severe, we could see more people moving away from high-risk areas, like Asian countries, to live in safer regions of the world.

What will it cost investors?

Some of the literature on climate change economics suggests that natural disasters could actually boost corporate productivity and promote growth in the long-term. This is because firms that survive the disasters will update their capital stock and adopt new technologies. This hypothesis that disasters stimulate growth is called “creative destruction”.

However, not everything supports that view. A recent study analysed countries’ physical exposure to the universe of tropical cyclones during 1950-2008. It found strong evidence that national incomes decline, relative to their pre-disaster trend, and do not recover within 20 years. This seems to be explained by the fact that disasters temporarily slow growth by destroying capital, but no rebound occurs because the various recovery mechanisms fail to outweigh the short-term negative effect of losing capital.

The analysis seems to support the “no recovery” hypothesis, finding that a one standard deviation in a year’s cyclone exposure lowers GDP by 3.6 percentage points 20 years later, setting an average country back by almost two years of growth.

In our analysis on 30-year returns, we have incorporated the impact of global warming on productivity to find that it will have an impact on long-run equity returns. Over the long term, productivity is a key driver of equity returns. Hence equity returns will be affected by climate changes through its effect on productivity.

Chart 6 compares our 30-year equity returns with and without global warming. It is clear that there will be winners and losers as a result of rising temperatures.