* This article was published on April, 17, some days before WTI oil barrel prices went down to negative for the first time in history.

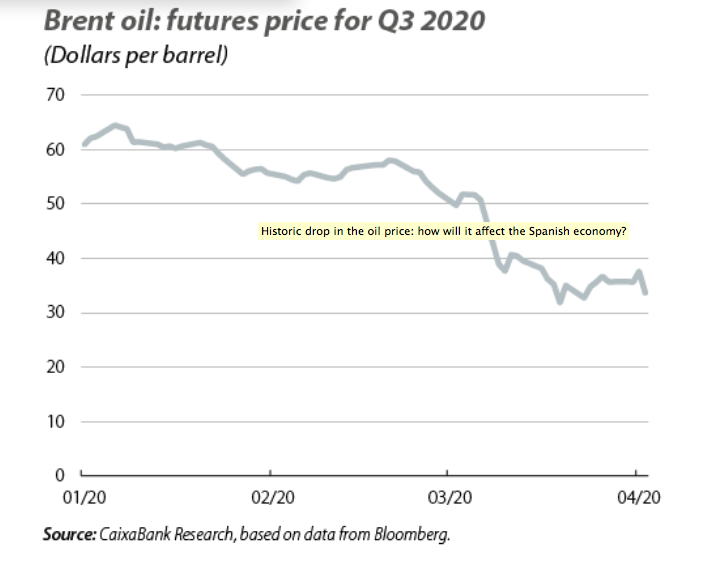

Caixabank Research | Last March, Saudi Arabia and Russia took investors and analysts by surprise by initiating a price war in the oil market. This war, coupled with the fall in demand that will stem from the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in the coming months, caused a historic decline in the price of crude oil: on Monday 9 March the barrel of Brent plummeted 10.91 dollars, down to 34.36 dollars (–24.1%, its biggest drop since 1991), and its descent continued throughout the month until it temporarily approached 20 dollars. Thus, we went from an environment in which the barrel of Brent was priced at around 60 dollars at the beginning of the year to fluctuating around the 20-25 dollar range. Moreover, these lower oil prices seem set to continuity (for instance, the 3- and 6-month futures price of a barrel of Brent stood at around 32 and 36 dollars at the end of March, respectively).

How does the oil price affect economic activity? A fall in the price of oil provides a boost to the economy of countries that are net importers of crude oil, as is the case for Spain. Cheaper oil equates to an increase in the real disposable income of households, such that it also supports aggregate consumption. In addition, companies’ production costs decrease, which favours investment. Finally, since the capacity for consumption increases not only at the national level but also at the international level, and in the short term imports (in terms of volume) are relatively unaffected by changes in the oil price, a lower price favours the trade surplus.

However, the health crisis that has gripped us following the COVID-19 outbreak will result in this boost derived from a lower oil price not being reflected in the economy, at least for the time being. The containment measures have led to a stagnation in industrial activity and in the movement of vehicles, so the demand for energy will show very little sensitivity to the fall in prices while economic activity and mobility remain restricted. In fact, our growth forecasts for Spain indicate a significant contraction of GDP in 2020, greater than those experienced during the Great Recession and the sovereign debt crisis, which will be particularly concentrated in the first and second quarters of the year.

The tailwind provided by oil will be felt when economic activity begins to return to normal

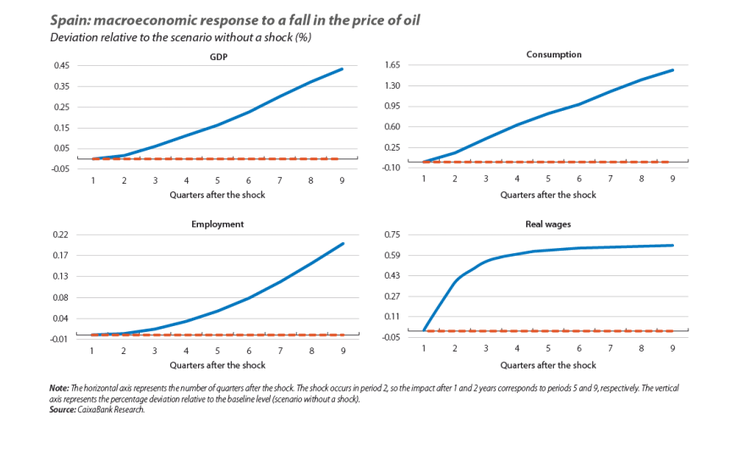

When the containment measures are finally lifted, the low oil prices may provide an additional tailwind to spur the recovery. CaixaBank Research’s macroeconomic model for Spain allows us to quantify how much a lower oil price will contribute to the economic recovery through the channels mentioned above (consumption, investment and the foreign sector). To carry out this analysis, we introduce into the model an exogenous reduction of 26.3 dollars in the price of a barrel of Brent, which corresponds to the difference between the futures price of a barrel of Brent for Q3 2020 that was registered in January (60 dollars) and that registered in early April (33.7 dollars), as shown in the first chart. In addition, we assume that the price will stand at 41 and 44 dollars at the end of 2020 and 2021, respectively, in line with the futures price for these two periods quoted at the beginning of April. The results of this simulation show that GDP would be 0.16% and 0.43% higher after 1 and 2 years, respectively. Other variables of interest, such as consumption, employment and real wages would be 1.57%, 0.20% and 0.66% higher after 2 years, respectively (see second chart).

Thus, the persistence of oil prices at around the 30-dollar mark could combine with the normalisation of mobility, the rebuilding of stocks and the materialisation of pent-up demand to drive the rebound in economic activity in Spain in the second half of 2020.