Alicia García Herrero (Natixis) | Against the backdrop of the recent reopening after three years of zero-Covid policies, the Chinese government, in the last government report of Prime Minister Li Keqiang during the Two Sessions, has set a GDP growth target of around 5% in 2023. Such a target is lower than our growth forecast of 5.5% for 2023, and lower than last year’s government target (5.5%). This is somewhat conservative if one considers the very large positive effect stemming from the simple fact that last year’s growth was very low (strong base effect). The question then is why such a conservative target.

First and foremost, the Chinese government does not want to run the risk of undershooting its growth target again, as happened in 2022. Even if consumption is recovering, external demand remains weak, and it is hard to know whether private investment will indeed rebound given doubts about the role of the private sector in the Chinese economy as well as an increasingly cautious sentiment by foreign investors. Furthermore, the real estate sector continues to be a drag on growth.

Secondly, the Chinese government does not seem to be willing to push overly lax fiscal stimulus to ensure higher growth. In particular, the fiscal budget deficit is set at 3% for 2023, which is slightly higher than last year (2.8%) but lower than 2020 (3.6%) and 2021 (3.2%). Most importantly, the issuance of a local government special-purpose bond is targeted at 3.8 trillion, which is only moderately higher than the average for the period 2020 to 2022 (between 3.65 and 3.7 trillion) even at a time when land sales are expected to continue to grow stagnantly. Finally, in terms of monetary policy, the government continues to use the same wording as in past reports, namely that money supply and total social financing will be consistent with nominal economic growth. This also means that, so far, no credit binge is to be expected to push growth beyond what will come from the positive base effect after the reopening.

Thirdly, the government’s push for a structural shift of the Chinese economy is still on the way. Over the last few years, tighter regulatory measures have been introduced to contain the financial risk and achieve more social objectives (green economy, food security, etc.) and it seems clear that such policies are here to stay based on the strong messages in the report.

While the growth target was moderately toned down, one special reality is that the government has raised the new employment target to 12 million, which was usually set at 11 million over the past five years (except for 2020, which was even lower, when Covid-19 first broke out in China). The lift of the employment target reflects the government’s concern about the job market, especially for young workers, whose unemployment rate reached almost 20% during the spring of 2022. In other words, the government wants to keep up the current employment growth momentum for 2023. However, the ambitious employment target also implies that the current growth target is not ambitious enough, because higher employment creation usually relies on stronger economic growth.

All in all, the 5% growth target is consistent with the current challenges facing the Chinese economy as well as the government’s more diversified objectives beyond economic growth, pushing for the Chinese economy to embark on a more sustainable growth path. But, job market pressure and the increased focus on creating employment implies that the government will still try its best to push for stronger growth (which can be higher than 5%), even though it may not want to make such promise at the early stage of the year, after last year’s disappointing experience.

China’s 2023 Government Work Report: Safe growth target contrasts with bold employment objective

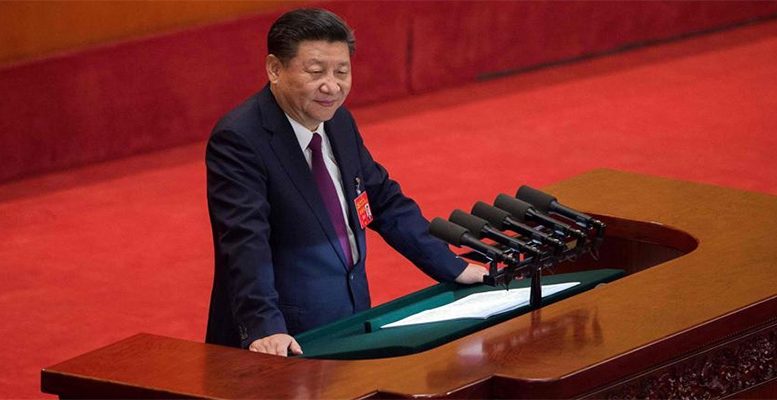

China's President Xi Jinping gives a speech at the opening session of the Chinese Communist Party's

China's President Xi Jinping gives a speech at the opening session of the Chinese Communist Party's