In January, inflation in the Eurozone jumped by 1.2 points to 0.9% year-on-year, largely due to the increase in VAT rates in Germany. Later this year, the ECB’s target inflation rate of 2% is likely to be exceeded. After the compression of some prices in 2020, the base effects are expected to be very strong. Some market participants might then recommend a less accommodative monetary policy. The ECB has no reason to react to a bump in inflation, but since Christine Lagarde has accustomed us to a convoluted message to please the “hawks”, we cannot exclude the possibility of the ECB getting muddled up in its communication.

As a result of the coronavirus crisis, economic indicators have experienced extraordinary variations. Business climate, activity and retail sales indices recorded unprecedented falls in the spring of 2020, then rebounded just as exceptionally during the summer. Price indices are no exception, but since it is customary to analyse them in terms of year-over-year change, it is only now and in the coming months that we will see atypical movements. The preliminary estimate of Eurozone inflation in January is a foretaste of this. It jumped from -0.3% to 0.9% y-o-y in January. Core inflation rose from 0.2% to 1.4%, its highest level since 2015.

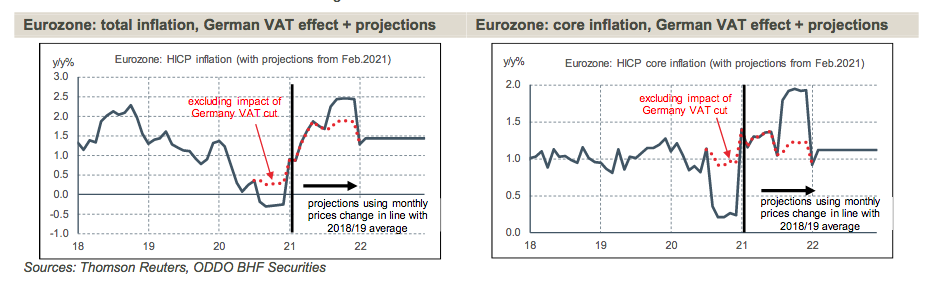

The sudden jump in European inflation does not reflect real tension on prices or wages but rather the influence of diverse technical or temporary factors. The most significant one is the 3-point rise in VAT in Germany on 1 January 2021, reversing the fall on 1 July 2020. Inflation is calculated using prices inclusive of tax. All other things being equal, a fall in VAT instantly pushes down the inflation rate, and vice versa in the event of a rise. The impact then remains visible in the inflation rate for twelve months. Thus, from July to December 2020, European inflation was in way underestimated because of the VAT shock in Germany. Conversely, from July to December 2021, European inflation will be overestimatedas the calculation will be made by comparison with a period when the price level was temporarily lowered. We illustrate this distortion on the total price index (chart lhs) and the core CPI index (chart rhs). The dotted red lines correct the shock on German VAT. For projections to 2021, it is assumed that prices will evolve on a month-to-month basis as was the case in 2018-2019, before the pandemic. This assumption probably has an upward bias as the considerable output gap created by the pandemic will not have disappeared, but our aim is first and foremost to show the general shape of the future inflation profile, with a bump developing throughout 2021 before flattening down again.

More anecdotally, two phenomena occur every January that may cause volatility in the price indexes. First, Eurostat updates the weighting of the various items in the price index to better reflect the structure of household spending (which was disrupted during thepandemic since some services became inaccessible). Second, at the start of each year, sales take place but the sales periods vary from one year to the next and from one country to another. This year, due to the health restriction on the activity of some shops, it is fairly difficult to measure the impact. These various effects are primarily a matter for the statisticians to handle and they should not affect the central bank’s analysis of inflation. Even so, the ECB’s communication will not be facilitated if inflation continues to accelerate strongly in the coming months.

On the one hand, the ECB is keen for inflation to pick up since it has been well below target for nearly 10 years now. Quarter after quarter, the inflation projections produced by the ECB staff forecast a return to or close to the target in two to three years’ time, but this return is constantly pushed back. It is tempting to conclude that the ECB does not take its mandatesufficiently to heart, in other words that its policy is not accommodative enough1.

On the other hand, the ECB knows the projected uptick in inflation is largely temporary. It surely does not wish to send a signal suggesting that the monetary policy has accomplished its mission and that it should therefore be normalised, or at least that the issue of normalisation needs to be debated. The members of the executive board (Lane, Schnabel) are quite clear on this point. And yet the recent speech from Christine Lagarde is not without ambiguity. At her press conference last month, she was careful to say that the PEPP might not be used to its fullest capacity, probably as a gesture of appeasement to the more “orthodox” governors. As we see it, these considerations muddy the ECB’s communication unnecessarily. If this supposed monetary “orthodoxy”leads to decisions that are bad for the European economy and no in line with the inflation mandate, it should not be given any scopebut consistently refuted.

To complicate matters, the debate around inflation is not only European it is also global. Having virtually ground to a halt in the first half of 2020, manufacturing needs to rebuild inventories. Prices of raw materials, food, industrial commodities and energy are now picking up. If demand returns to pre-crisis levels in the next few months, sectors that had scaled back capacity could be hard pressed to keep up easily. This could cause short-term tensions, at least at the production stage (the repercussions for consumers could be offset). Distinguishing in real time between a cyclical acceleration and the potential beginnings of a new inflation regime will be difficult. As a rule, the tell-tale factor is the labour market but, here again, because of the pandemic, the message is confused. European unemployment has not risen by as much as might befeared in view of the collapse in GDP (thanks to short-time working schemes) but this could then give the impression, which is misleading in our view, that full employment is not that far off.

The ECB, unlike the Fed, has yet to finalise its strategic review, but it is likely that the result will be relatively similar, which would imply that the ECB ties its hands and maintains an accommodative policy even if inflation were to durably exceed its target. As Jerome Powell defusedthe debate on early tapering in the US, we would prefer that Christine Lagarde refrain from ambiguous comments on the future direction of ECB policy. All told, the economic cost of the pandemic has been heavier in the Eurozone than in the rest of the world. The exit from the crisis appears more fragile here, particularly due to the slow rollout of the vaccination campaign. Inflation has been a long way from its target in the region. All of these elements suggest that the real risk for the Eurozone is that inflation remains too low rather than too high. This justifies having a dovish and not a hawkish bias.